A media visit organized by Iceland Cool results in winter travel coverage in BBC Travel for client Hotel Ranga in an article entitled: A Rare Sighting of the Milky Way.

BBC ran a feature article on Hotel Ranga written by Roseann Lake who visited the hotel in December as a result of the #IcelandChristmas Press Release. BBC Travel has en estimated monthly audience of 357 million views.

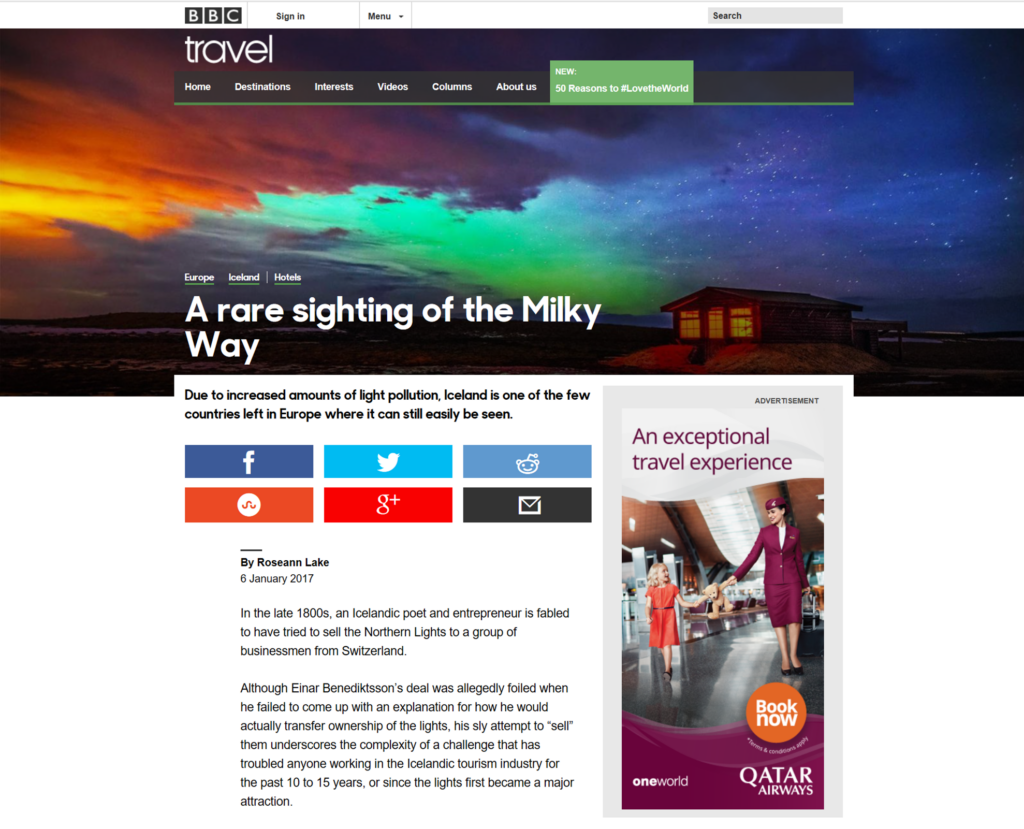

BBC Travel: A Rare Sighting of the Milky Way – by Roseann Lake

Due to increased amounts of light pollution, Iceland is one of the few countries left in Europe where the Milky Way can still easily be seen.

Also known as the aurora borealis, the Northern Lights are notoriously coy. A delicate mix of high solar activity (which yields electrically charged particles that collide with gases such oxygen and nitrogen) and clear skies is required to see them. And while Iceland is indeed one of the most spellbinding places on the planet to take in their ethereal swirls and streaks of neon green, fuchsia, violet and aquamarine, there are days, weeks even, when they just don’t appear.

For Friðrik Pálsson, owner of the Hotel Ranga in southeast Iceland, this was initially a problem. “The Northern Lights are easy to sell, but they’re very hard to deliver,” he said, echoing the travails of his scheming compatriot.

“I felt bad because it seemed as if our guests weren’t enjoying the skies as much as they should,” he said, of nights when the lights failed to appear. “I wanted to give them another way to appreciate the darkness.”

Pálsson, who took over ownership of the hotel after a 30-year career in the seafood business, knew little about Iceland’s night sky. So he called someone who did: local astronomer Saevar Helgi Bragason. They both agreed that the Hotel Ranga’s remote location, far from the light pollution of Reykjavik, made it not only a prime location for viewing the aurora (when it did appear), but also a magnificent blanket of some 2,500 stars – all visible with the unaided eye on clear evenings. While these stars didn’t go unnoticed by hotel guests, they failed to capture their attention as much as the ever-mercurial Northern Lights.

That all changed starting in 2013, when Pálsson enlisted Bragason to help him build an observatory on the hotel grounds that today houses two of the most powerful telescopes in Iceland: an 11in Celestron Schmidt-Cassegrain and a TEC 160ED APO refractor on an Astro-Physics 900 mount. Located in what Pálsson fondly refers to as the hotel’s “red light district”, given the trail of red reflective lights that faintly illuminate the 150m path to it from the hotel, every element of the observatory’s design was meticulously chosen, including the ingenious roll-off roof that allows for a panoramic view and is activated with the flick of a button. Motors grind, chains shifts, and roughly 45 seconds later, a glittering sky is unveiled.

“I can’t wait until Betelgeuse explodes!” said Bragason, who has contagious curiosity for the cosmos. He animatedly explained to the laymen stargazers gathered in the observatory that “Betelgeuse” is a star on the upper right shoulder of Orion that is expected to explode any day now – which in astronomer speak means anytime between now and the next 100,000 years. “When it does, the sky will glow a magnificent shade of orange,” he said. “I cross my fingers every time I look into a telescope in hope that I’ll see it.”

Bragason usually begins his sessions – which take place on every clear evening at 9pm and are free and open to all hotel guests – with a playful mix of astronomy and mythology. He explained how, in a fit of passion, the notoriously flirtatious Zeus became enamoured with mere mortal Alcmene, and together they conceived a son named Hercules. Hoping to make his son immortal, Zeus secretly attached him to the bosom of his sleeping wife, the goddess Hera, who awoke mid-suckle. Realizing that the child was not hers, she pushed him away and her milk squirted across the sky, creating the band of light and stars known as the Milky Way. Due to increased amounts of light pollution, Iceland is one of the few countries left in Europe where it can still easily be seen.

Laser-beam pointer in hand, Bragason went through the overhead constellations, which might include Cassiopeia, Cepheus and Andromeda – another derelict family trio that got itself into trouble, with Poseidon in this case, leading to drama with Perseus and the eventual beheading of Medusa.

Depending on weather conditions and the orbit of certain planets, the stories can be peppered with bewitching glimpses into the night sky, such as the moon and its craters, and Cassini’s Division, the largest and most prominent gap in the rings of Saturn. “We can sometimes even see clouds on Jupiter,” Bragason said. “It’s wild to be able to see the weather conditions on another planet.”

The telescopes have all the equipment that an avid astrophotographer might require, though most guests are simply happy to position their smartphones behind the eyepiece and snap an image. In the summer, when Iceland has nearly 24 hours of light, the telescopes are used to look at the sun, which Bragason is particularly fond of, especially during an eclipse. “As an Icelander, I’ve seen a few spectacular volcanic eruptions, but I promise that solar eclipses are way more beautiful,” he said.

Though dedicated primarily to the hotel – which has outdoor jacuzzis heated with geothermal water where guests can soak and stargaze, if they prefer – Ranga’s observatory is also open to student groups and the Amateur Astronomical Society of Seltjarnarnes, of which Bragason is president.

“It’s important for everyone to know a little bit about what’s above them. Something about peering into the night sky and seeing stars that are 250 million light years away really changes your perspective on the insignificant things that bog you down on a daily basis,” he said.

Recent Comments